WaveCel isn’t just some expression, it’s a company and brand name. The company cares about security, specifically for our heads when exposed to potential danger in sports, work or whatever activity; it develops products that enhance security in helmets. Anon is the exclusive partner of WaveCel in snow sports which offers obvious benefits but also poses its own challenges. For example, WaveCel is far less known than “Titanal” (a brand name for a specific type of aluminum in skis) or MIPS (a comparable tech that also strives to improve safety in helmets but is used by many different producers of snow sports helmets—including Anon). In this article, we strive to explain why tech like WaveCel or MIPS is really essential, what makes WaveCel special and why it may be the best available tech in this respect at the moment. Prepare yourself for a deep dive.

Gear

HighlightAnon’s exclusive feature

The Story of WaveCel

Helmets are devices to prevent head injuries, obviously. More specifically they are devices to prevent brain injuries as the brain is arguably the most important part of our heads. But what type of brain injuries? Of course, when you think of a warrior sinking his axe into the head of an opponent in the old times or in a computer game, the brain will suffer damage. A rock in a ski crash could do the same—in which instance the hard shell of helmets safeguards us. However, those incidents are very rare and far from being the most prevalent type of brain injuries. The most prevalent type of brain injury is trauma which often happens without even a sign of injury at the outside of the head.

There are different grades of severity in brain trauma, the least one being concussion. Yes, good old concussion. While most concussions luckily go away over time, they pose a bigger danger to our health than long thought, specifically when they are incurred repeatedly or aren’t treated correctly. Just search for post-concussion syndrome to get more info but that’s a topic for another article. (You could check out the interview with Lisa Zimmermann in our book Ski Stories Volume 5 for an unfortunate case of post-concussion syndrome.)

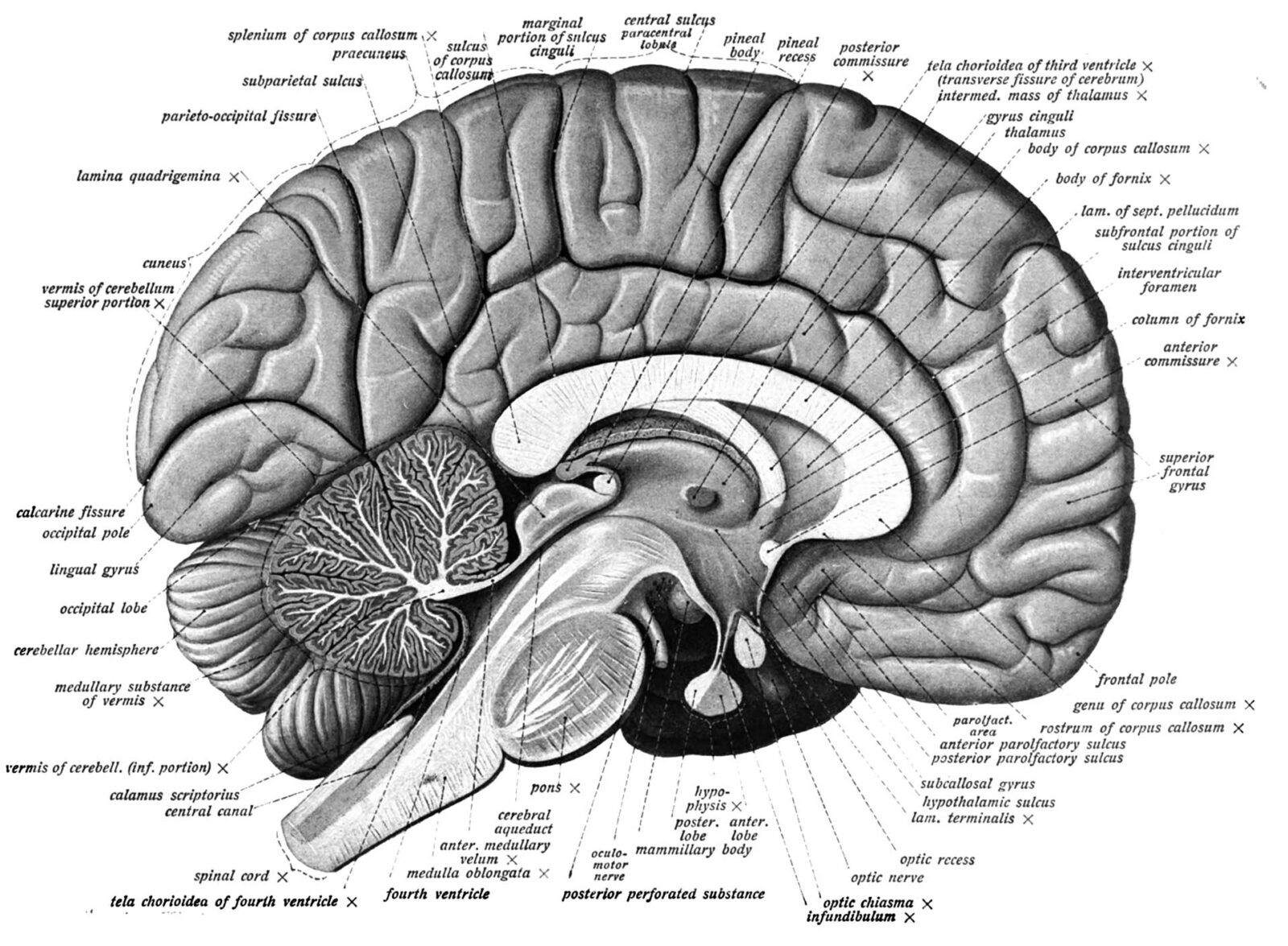

The funky thing about concussions is that it’s not fully clear what they actually are. Likely they can be linked to a variety of little damages to the brain. Those damages can occur when the brain gets compressed but also when there is shear stress. Our brain is a complex structure of roughly 90 billion neurons and about as much neuraglia (cells that support the neurons) which sit inside the skull within the cerebral fluid. This fluid acts like a cushioning both towards linear and rotational acceleration. Linear cushioning is obvious to us, it’s like falling onto a soft bed instead of the hard floor. Rotational cushioning is a bit harder to grasp. To understand what rotational acceleration can do, visit WaveCel’s website and watch the “Egg Effect” video (just scroll down a bit).

Recent research suggests that in the majority of incidents, where concussions occur in a sportive scenario despite wearing a traditional helmet, rotational acceleration is the driving force compared to linear acceleration. But when does rotational acceleration occur? Well, basically every time you hit with your helmet at something other than perfectly straight on. Take a ball and dop it to an inclined surface. It will bump off at an angle, but it will also start to rotate. You could go and watch a curling match, easily doable at the current Olympics. There are those overhead cameras showing how the curling stones collide… So every time you crash while skiing and your head hits something, rotational acceleration is at play because chances are slim you hit that obstacle or the ground perfectly perpendicular.

Now we understand rotational acceleration and why it’s important to reduce it. But how can it be reduced? As with cushioning for linear acceleration, the aim is to stretch the change of motion over time. We need to make for some room for rotational motion and use this room wisely. For example, go back to the fall on the bed in linear cushioning. Instead of changing our velocity to zero in an instant like when we fall on the floor, the bed will break down the motion much slower and we sink into the bed in the process. Ideally, all the motion is gone before we hit through the mattress on the slants and for this the mattress needs the right density.

To cushion rotational acceleration, we need to create room for angular motion and we need to slow down the motion while moving through this space. This is where WaveCel comes into play. It enables the head to rotate relative to the helmets outer shell and at the same time works against this motion with a defined force, stretching out the acceleration over time and thus making it way less harmful to the brain. This is achieved through the WaveCel structure: an assembly of a multitude of little springs which can move relative to one another in 3D. As a consequence, the WaveCel structure not only compresses like classic cushioning foam in a helmet, it can also shear and enable rotational motion. Additionally, it poses a force against this rotational motion, slowing down the rotational acceleration.

Is WaveCel the only tech with this functionality? No, since there is for example MIPS, a relatively widespread and well known asset for helmets. In contrast to WaveCel, MIPS simply enables the rotational motion by introducing a sliding plate between the outer shell of the helmet and the inner cushioning. This enables motion, but to work as a damping device it also needs to slow down this motion. In order to do so, MIPS simply relies on friction, like when you drag something solid over a table. There are two downsides of friction as a method to slow down motion. Firstly, it is less controlled (unless you employ a elaborated mechanical system like the brakes on your bike do) and secondly it’s not working progressively as classic cushioning foam for linear acceleration or WaveCel for linear and rotational acceleration. Progressive increase of force against motion is preferred since it allows to effectively address a wider range of acceleration.

But before we look into more details of how WaveCel works and how it compares to other methods of countering rotational acceleration, lets quickly look at WaveCel as a company. It was founded by a scientists and a doctor in Portland, Oregon. The scientist, German native Michael Bottlang, earned his PhD in Biomechanics Engineering at the University of Iowa and has gathered decades of experience and expertise in dealing with all kinds of orthopedic trauma. The doctor is Steve Madey, a board-certified hand and microvascular surgeon who studied at Columbia Medical School and had a residency at the University of Iowa. Both Micheal Bottlang and Dr. Steve Madey eventually moved to the Northwest and have collaborated on the improvement of helmet technology at the Legacy Biomechanics Laboratory for the past 15 years. WaveCel is a major outcome of this collaboration.

WaveCel isn’t your average product or short-lived invention, it’s a serious piece of tech with lots of scientific development involved and clear advantages proved in scientific studies. For details, look at the research article “Impact Performance Comparison of Advanced Snow Sports Helmet with Dedicated Rotation-Damping Systems,” published 2021 in the “Annals of Biomedical Engineering.” It compares the performance of three helmets, the Anon Logan WaveCel, the Smith Maze MIPS and for reference the regular Smith Maze, the same helmet simply without MIPS (the Logan doesn’t exist without WaveCel). For the study, all helmets were dropped with two impact speeds on a 45° inclined surface and resultant accelerations of a head dummy in both linear and rotational direction were measured and calculated. Three different impact areas at the front, side and back of the helmets were used.

Before we summarize the results, let’s just state that testing helmets is a difficult task. First of all, what is a realistic crash scenario and how can this be mimicked in a laboratory setup? At what circumstances do you test? Fun fact: Helmet tests, specifically for the classic European (CEN 1077) and American (ASTM F2040-18) helmet classifications, are performed at “normal” conditions (17-23°C, 25-75% relative humidity) which are definitely not regular conditions in real snow sports. Most importantly maybe, what kind of head dummy do you use and how do you fit it into the helmet? There are different “standard head dummies” and depending on which one you choose, your test results could be different. Very likely your specific head will be different than any standard head dummy, as will be your helmet fit. That’s absolutely not saying that those tests are useless. Quite to the contrary, but they also don’t offer a perfect truth. So whenever you come across a test and one helmet is slightly better than the other in that test, I would assume them to be comparable as far as their safety potential is concerned. If there are big differences in the test, there will be differences in reality, too.

Back to the test results. For linear acceleration with a front impact, all three helmets were basically the same. For linear accelerations with impact at the side or at the back, both Smith helmets were really the same—in one case the one with MIPS was ever so slightly better and in the other case the one without MIPS—while the Anon was better in both those cases, but all helmets performed well in all scenarios. For rotational acceleration, it was a different story. With front impact, the Smith Helmet without MIPS was clearly subpar to the two helmets with devices to decrease rotational acceleration. At the slower impact speed the Smith with MIPS did slightly better than the Anon with WaveCel, at the higher impact speed it was the other way round, but both were very close. For side impact, the difference between the Smith without MIPS and the other two was smaller, but it was still existing, while both helmets with rotation-damping were again similar (interestingly, this time the Anon did a bit better at the slower impact speed and vice versa). The big difference came when the impact area was at the back of the helmet. Here the difference between the Smith with and without MIPS wasn’t big—the one with MIPS still did a bit better—but the Anon with WaveCel was now clearly better performing than the other two.

An important aspect of all the testing was that the highest acceleration forces with respect to concussion risk occurred when the impact happened at the back of the helmet. The authors of the study drew comparisons based on a field study with injury metrics from over 63,000 impacts recorded from instrumented football players which combined the probability of concussions due to linear acceleration and due to rotational acceleration. For the scenario with the higher impact speed and the impact zone at back of the helmet, the concussion probability was around 90% for the Smith helmet without MIPS, around 65% for the Smith helmet with MIPS and only around 10% for the Anon Logan WaveCel. Now that’s definitely a relevant difference. For all other scenarios (front and side impact at both speeds and back impact with the lower speed), the concussion probability was below 10% for both helmets with rotational damping, while the helmet without such a device still had around 20% for a rear impact and lower impact velocity as well as 30% for a side impact and higher velocity.

If we want to draw conclusions from these test results, I would say, firstly always opt for a helmet with a device for rotational damping, be it WaveCel, MIPS or any other. Secondly, an important outcome is that WaveCel works better universally as a rotation damping device compared to a more simple sliding device like MIPS. It’s self-evident to conclude that this is due to its 3D structure and how that works to reduce rotational acceleration. It’s not something that can be concluded in a strictly scientific manner and the difference could be smaller for another implementation of the MIPS system in a different helmet. However, since that is impossible to predict from the outside, the WaveCel tech simply provides more peace of mind when it comes to concussion protection.

Are Anon Helmets with WaveCel the ultimate helmets for snow sports then? Well, they definitely have some good arguments, but a helmet is more than just one feature. There are also some potential disadvantages with WaveCel, for example, it is thicker and heavier than a simple device like MIPS. On the other hand, the WaveCel device also acts as cushioning for linear acceleration and thus eliminates the need for cushioning foam other helmets employ, enabling the helmet to be lighter and slimmer again. I could test the current iteration of the Anon Logan WaveCel and it feels very comfortable on my specific head. How helmets compare in size and weight, isn’t decided by one feature alone, though. What’s way more important anyway is the fit of the helmet. A helmet with a good fit will protect better than a helmet with a bad or very loose fit. At this point, a word to everybody opting to use a big beanie underneath their helmets: You counteract the function of devices like WaveCel or MIPS. Even though you might think, you increase the damping with the beanie, you actually reduce the protection your helmet is capable of with a good fit.

So here you have it, the break-down of what WaveCel is. You might ask yourself, why haven’t I have heard of WaveCel before, then? Well, Anon has secured exclusivity with WaveCel in the snow sports sector. What might be a good decision from a sales perspective, poses some problems from a marketing standpoint. Anon is the only one to wave the flag in snow sports since WaveCel itself isn’t communicating in the same way Gore is for Gore-Tex, the one product that managed to make a name for itself in sports communities and beyond despite the fact that it’s not sold to the consumer as a stand-alone product—it’s just part of a jacket like WaveCel is part of a helmet. Harking back to my example from the introduction, do you actually know what Titanal is? I guess that’s a story for another time…