Stories

Sam Anthamatten: Freeriding, Alpine Style

This article has been adapted from the Winter 2018 print issue of Downdays Magazine. Use the mag finder at the bottom of this page to find a copy in a ski shop near you.

Interview: Klaus Polzer | Photos: Tero Repo

He’s sort of like the Swiss Army knife of freeriding, but not simply because he comes from the foot of the Matterhorn. Sam Anthamatten can ride the gnarliest big-mountain lines, reach their starting points without external help and correctly assess the risks along the way. He doesn’t just descend lines, but rides with speed and style, sometimes even with a freestyle trick tossed in for good measure. His first passion was climbing, where he’s accomplished noteworthy feats, before he first found his way to freeskiing as a freestyler. In the mountains surrounding his home of Zermatt, all of these influences melded together to produce a rare all-round talent whose skills range far beyond his mountain-guide certification. Consequently, even as he’s occupied the spotlight as an athlete on the Freeride World Tour and for the cameras of major movie productions, Sam is also often busy behind the scenes. In the coming season he’s far more focused on pursuing his own projects, as he reveals in our interview.

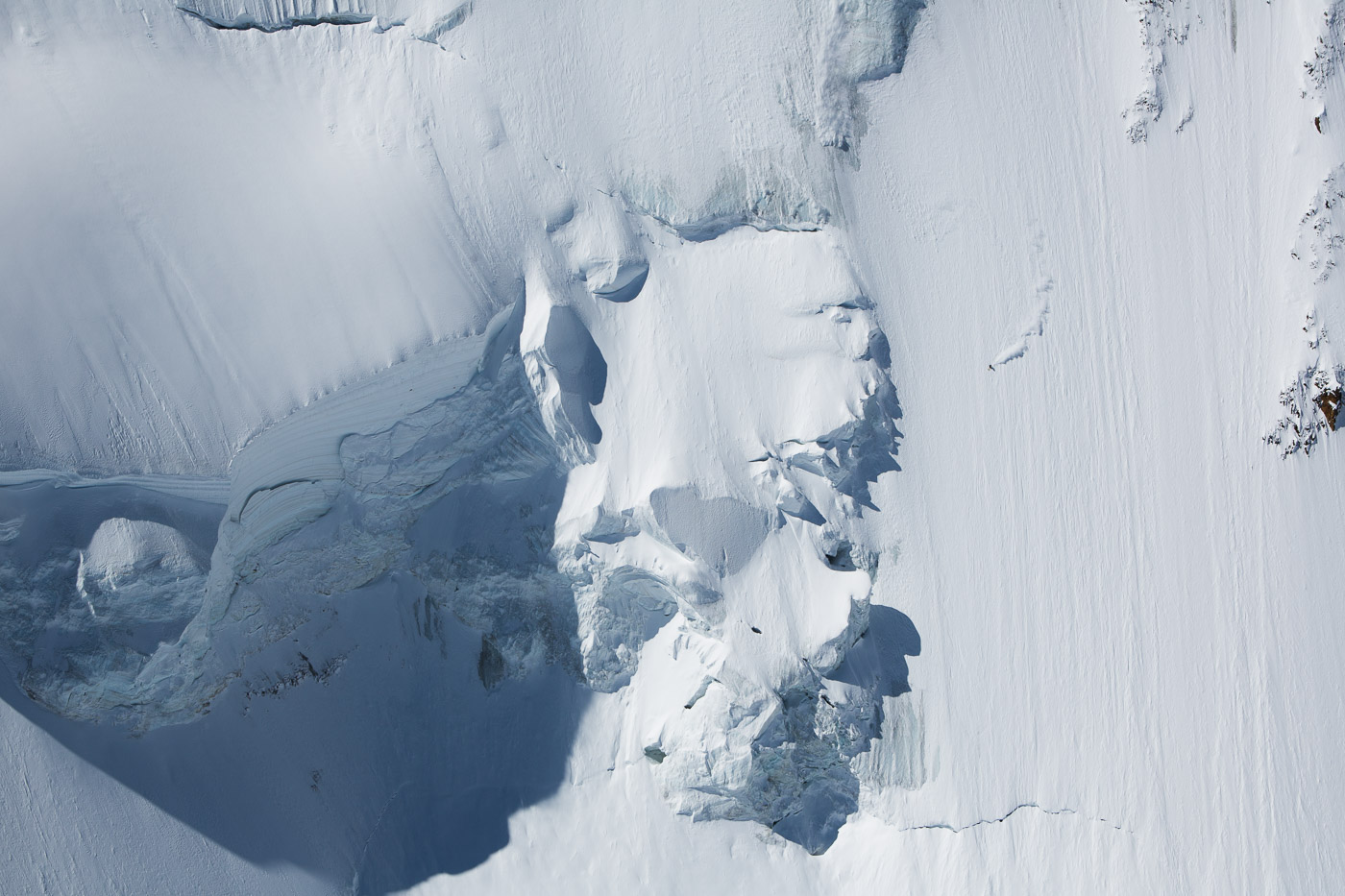

No stranger to exposure: Sam tackles a technical Georgian line.

Hi Sam, how was your summer? Did you go skiing, or just mountain climbing?

This summer I was just mountaineering, since my winter basically lasted until the middle of July. I had a film project with The North Face in the works, skiing Ushba in the Caucasus, which took much longer than originally planned. My season lasted from mid-September until the middle of July and after that I’d had enough of skiing for a while. I spent the summer at home in Zermatt, which was really nice. I went climbing, mountain biked a lot, and also did some work as a mountain guide. In the fall I went rock climbing in America, because climbing is still very important to me, and I wanted to check off a few really good routes.

Tell us about your Ushba project!

Ushba is a beautiful mountain in Georgia. At around 4700 meters it’s not the biggest, but still one of the most spectacular mountains in the Caucasus. It’s similar to the Matterhorn from my home. We wanted to do a ski descent of Ushba, but unfortunately it didn’t work out. I’ve seen pictures where the mountain really had a lot of snow, but last winter the conditions were never quite right. We actually wanted to make an attempt in May, but there was too much bare ice. We delayed until June and finally said, “Come on, let’s just try it!” But it turned out that we were too late. The temperatures warmed up so fast that any new snow melted and turned into ice. But it was still a good project and I think it will be a good film as well.

In the late season of 2017, Sam headed to Georgia with a crew from The North Face in an attempt to ski the remote 4710m peak of Ushba.

Has that project been checked off for you now?

No, definitely not; not in the least because Georgia is simply a tremendous place. I’m definitely going to make another attempt at Ushba when the conditions are better, and I’ll undoubtedly be going back to Georgia on other trips as well. The mountains there are spectacular and the snow conditions can be fantastic. I was there twice last winter, the first time in late winter to explore the area and do some normal ski filming, both for the Ushba project and the “Steep Series” campaign for The North Face. The conditions were perfect, as good as Alaska but with a lot less going on. Also, Georgia is just a two-hour flight from Europe, so I’d rather fly there than to Alaska!

You’ve already been in front of the camera for some major productions, including MSP, while traveling around the globe. Last season you also filmed at home in Zermatt. Is it easier to film on your home turf?

I filmed together with Johnny Collinson for the Faction movie This Is Home. At first we were at Johnny’s home in Utah where he showed me his mountains, then he visited me in Zermatt and we rode some lines there. That was an interesting concept. I’ve filmed in the mountains around Zermatt a lot before and I always felt that it was more stressful than going on a trip, because I feel so much more responsibility for what gets done. It was particularly hard last season since we had a very bad winter and never had really good conditions. Of course, I’m not stoked when I’ve got Johnny Collinson as a guest and I can’t show him the best lines because the snow isn’t there. Additionally, when working at home I’m usually involved in the organization. I basically led the shoot with Johnny, which meant quite a bit of work on the side. On the other hand, it’s cool when you can show the world how great your home is. The mountains of Zermatt, and the Alps in general, are the best place in the world to go skiing; at least when they’ve got snow. You really don’t need to go anywhere else.

Despite the old mountaineering rule of always staying on the ground, Sam really enjoys catching air.

As a mountain guide you’re often involved in projects not only as an athlete, but in other functions such as line-picking and safety. La Liste with Jérémie Heitz as well as the Freeride World Tour come to mind. Doesn’t that make it more difficult to focus on your performance?

First and foremost I see an advantage in being a mountain guide, because due to the training and experience working as a guide, I have a better grasp on risk management in general. That helps me as an athlete as well. On the other hand, it’s definitely a double burden. You always see the risks when you’re out with someone, and as a guide you can’t just push those concerns to the side. The problem is that even when I’m filming with an experienced skier like Jérémie Heitz and something happens, then the responsibility always falls on me as a guide, unless there happens to be another guide there who’s specifically responsible for safety. Because of that, I’m increasingly cautious about who I go filming or even just skiing with. It has to be people who behave responsibly and aren’t a liability for me. That’s also why I’ve decided not to ride in any contests this season. If something like the Skiers Cup happens again, maybe I’ll do it spontaneously, but it’s not planned. I’d rather focus on my own projects this winter.

Can you give away any details about your coming projects?

I have a few ideas for the coming winter, but I need to talk about them with sponsors first, so I can’t say anything yet. But I can say that I’m planning a new project with Jérémie Heitz that will span three years. The idea is similar to La Liste, only we’ve looked for mountains around the world this time; some 5000- and 6000-meter peaks, all with a pyramidal form and great descents. For that we’d go to Peru, China and also to the Caucasus, to name a few. But we’re still involved in locking down the financing, so it might be a while until the action in the snow gets started.

You said that you’d do Skiers Cup again, but that you don’t want to do the Freeride World Tour. Why not?

The Skiers Cup is simply a great concept. It’s the best event that I’ve seen so far. If there was a chance that it would happen again, I’d love to be there. I can also imagine doing the Freeride World Tour again in the future, but I’ve done that now for four years and need a break. I also think that the Freeride World Tour needs to reassess their concept somewhat… but the organizers are already doing that, anyway. For example, I think it’s good that Japan is a new part of the tour this season, although—or maybe because—the terrain there is a lot smaller than something like the Bec des Rosses. Sometimes the contest windows drag on for too long and I don’t understand, when the conditions at the Wildseeloder are terrible, for example, why we don’t move to less extreme, more varied terrain where we can put on a better show. I think that more people would identify with the contests if they weren’t so extreme. The Skiers Cup was a very good compromise and was also very well received.

The big faces around his hometown Zermatt are a natural theater for alpinists and hardcore freeriders. Here, Sam charges down the Hohberghorn.

How do you see the future of freeriding in general?

I think that the sport is developing in a good direction, even if the boom isn’t as big as it was three or four years ago. There are more people going out into natural terrain, but the accident numbers are declining, which is a good sign. The current trend is going in the direction of free touring, which I like a lot. It’s closer to nature and the quality of the experience remains intact, even if you’re not doing anything extreme. I think that our sport has a great future ahead of it, particularly here in the Alps. Where else can you access such great descents so easily, and have such in-depth information about avalanches, routes and weather? I notice that most of all when I’m traveling in a faraway place like China. We’re spoiled here in the Alps and honestly, I think we have a real paradise right on our doorsteps.

With all your achievements, have you become something like a celebrity in Zermatt?

Zermatt is a small place, so everyone knows everyone anyway. I wouldn’t know when one becomes a celebrity; my social environment is important to me and I always greet everyone that I know. Naturally it’s nice when you receive recognition for what you’ve been doing all winter, but what means the most to me, at times like when I’m at a film premiere and see that I can inspire people. I definitely don’t need to be portrayed as a hero. At the end of the day, I pay for my beer just like everyone else, and that’s the way it should be.